Challenging Students During a Challenging Time

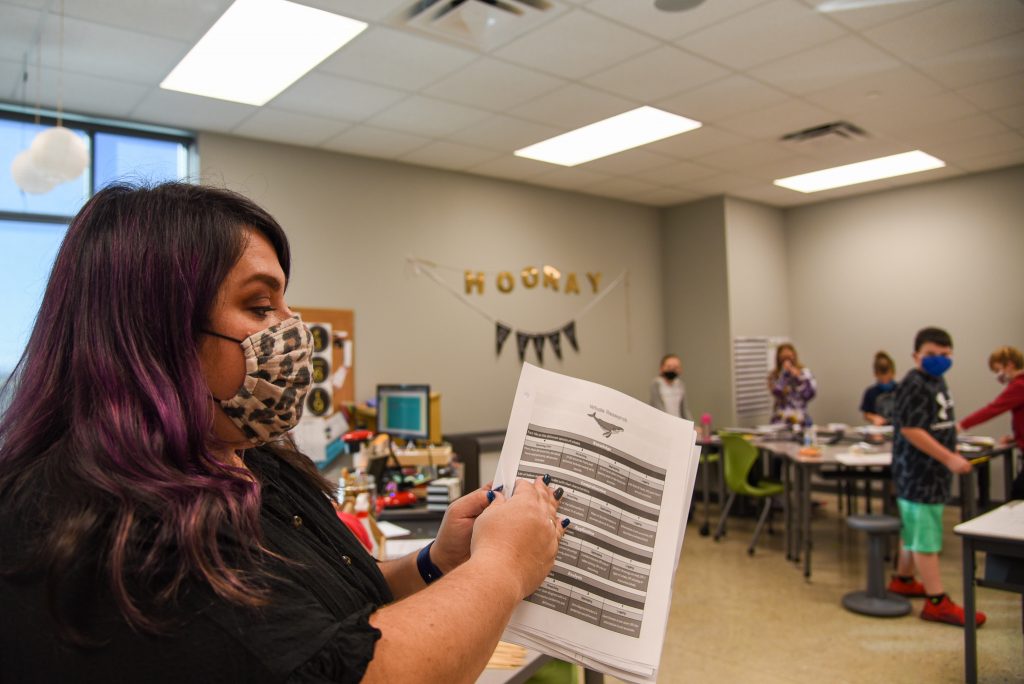

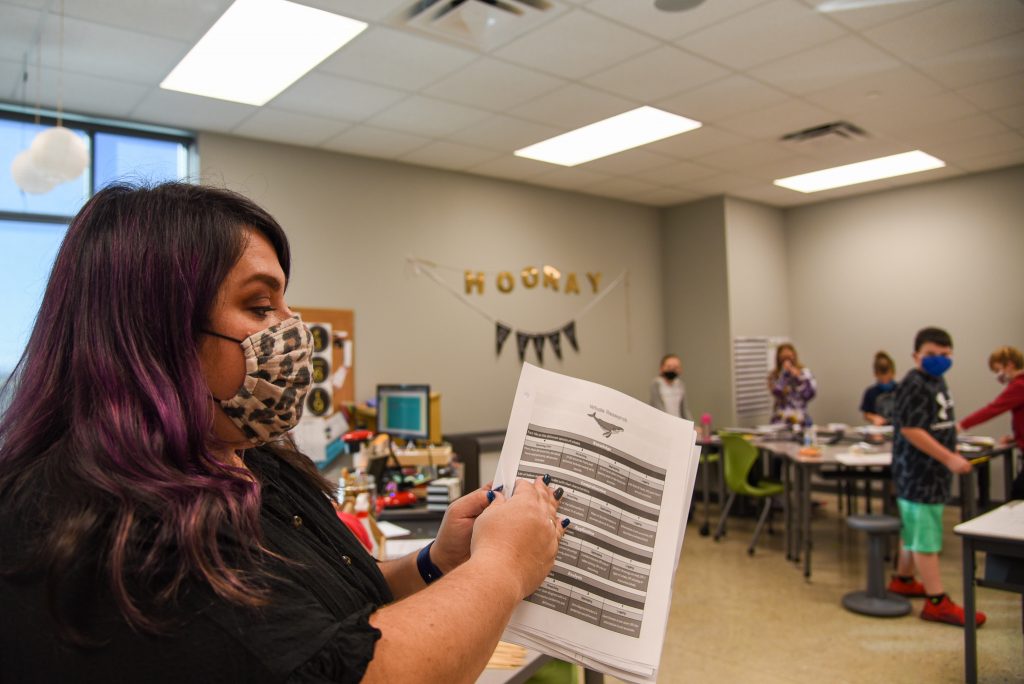

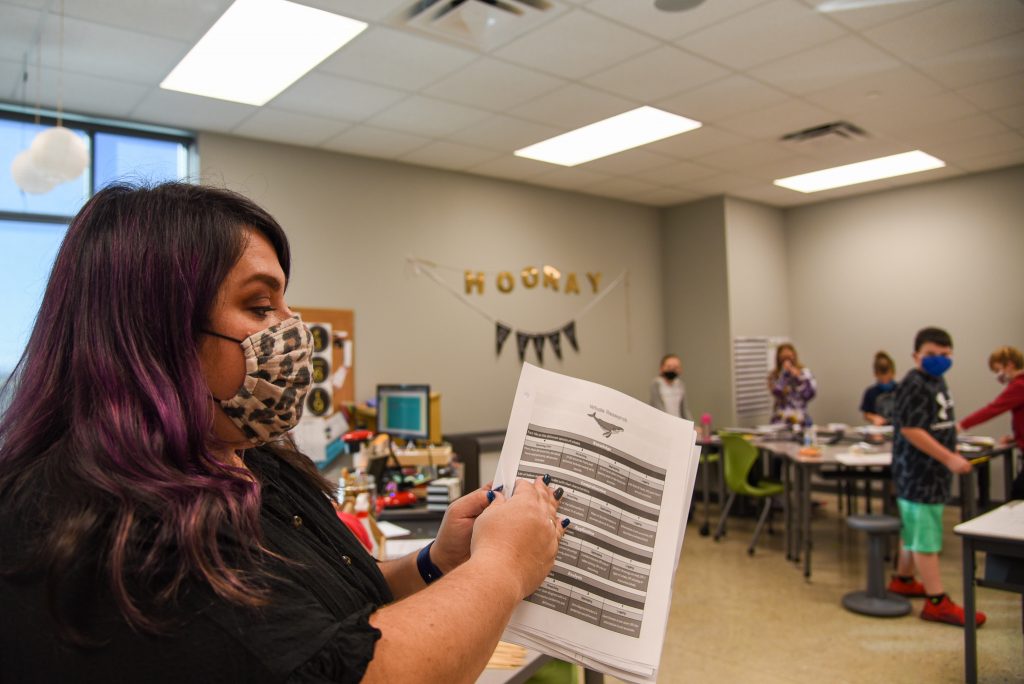

On a recent Tuesday, one of Ashley Rieske’s fifth grade classes is learning about whale flukes. Through online research, the kids find out each whale tale is unique, but the lesson doesn’t end on the web. The information they learn is applied into hand painted killer whale tale sculptures.

“We give them a different experience than what they get in their regular classrooms,” Rieske said. “We’re encouraging them to think in different ways.”

As the Rogers School District’s REACH Coordinator, she splits her time between schools. In the lower grades, Rieske gets 30 minutes a week with all students to work on creative thinking or problem solving. Those schoolwide classes help to identify future participants for her pullout program serving gifted 3rd 4th and 5th grade students.

“We get to come in and work on enrichment type activities and a lot of it too that most people don’t realize is social emotional,” she said. “They come and connect with other people that think like they do; to see that, ‘Oh I am different than everyone else, but there are people like me, just not maybe a ton of them in my class.’”

The isolation kids can feel in homeroom can also be exacerbated when educators focus on students who need more help.

“Our gifted kids often get overlooked just because of time,” she said. “They’re doing ok in class so those are the last kids we get to because we’re trying to help pull these other students up to where they need to be.”

Rieske also provides a safe place for students to struggle with content so they aren’t blindsided by more challenging material in later grades.

While an average learner may fail several times before reaching a target, many of Rieske’s students quickly pick up new concepts and don’t have the same experience.

“They don’t know how to fail and it’s middle school or high school before they hit things and don’t know how to cope,” she said. “We try to set up situations in our classrooms where they can have a safe failure and we can help them work through those social emotional issues and teach them that learning process.”

She’s also tasked with providing a literal safe place to hold class thanks to the coronavirus.

“Everybody is exhausted and just that constant worry of, ‘Am I keeping my kids safe? Am I doing what I need to for them?’’ she said. “We’re doing our best but our situations aren’t always ideal.”

Because her students are from different homerooms, they are stationed in socially distant clusters around the room. While it’s impossible to keep them apart completely, Rieske says they’re doing their best, and she uses technology to help students connect while saying physically separated.

“They were getting tired of working with the same kids all the time because that’s who they were around,” she said. “We use google meet. Even though we’re sitting in the same room, we can’t sit together so we do breakout rooms and mix up the people they’re working with. It was just research, but they thought it was the best thing ever because it was just different people.”

Rieske feels comfortable with technology but says this year has been challenging. In addition to all the normal daily activities, educators are constantly learning new software and experimenting with new ways to share information.

“I’m doing so much more generation of content,” she said. “I’m taking these lessons I’ve already done and trying to develop them into something that we can sit at our desks and do but still have the same experience. It’s almost like everybody is a first-year teacher again. How do I do this digitally? How do I keep them safe, but keep as close to the same experience as they would normally have?”

The virus is also making organizing more difficult. Rieske took the helm of the Rogers Education Association two years ago and says the plans she and her officers created to help grow the association got thrown out the window when COVID arrived. Plans for membership drives were replaced with crisis communications and public awareness efforts.

“The first thing we did that really got people’s attention was that we put out a letter back before schools shut down,” she said. “We wrote a letter and posted it on Facebook. I was hoping to reach a couple hundred people, and it was up to thousands just by the next morning. We started getting phone calls from the local TV stations, but I think that was what got the ball rolling with a lot of our members, like, ‘Oh, our local association is here. What can we do to help?’”

She said that engagement paid off, with the district listening to members’ concerns and modifying reopening plans. However, not being able to gather in person is a problem.

“We’re just kind of trying to find our footing,” she said. “ZOOM’s great and it’s a way to do things, but it doesn’t have that same connection that you have in person and I think everybody is kind of ZOOMed out.”

Rather than piling another video call on top of PDs or staff meetings, Rieske started writing and sharing detailed recaps of school board meetings.

“I’m trying to form connections in any way I can,” she said. “They’re pretty hungry for information. It helps everyone feel like they’re more in the loop with what’s going on.”

She thinks more educators are seeing the value of the association, and even though a virus may have been what brought them in, AEA has much more to offer.

“You can join the association and help us be a voice towards these things we’re asking for and trying to navigate,” she said. “I think if people slow down and realize, ‘Oh! All thes

e things I’m passionate about, AEA is working on and I can come be a part of this,’ they understand the benefit of working to

gether.”